|

An Interview with Máire Ni Chathasaigh (pronounced Moira

Nee Ha-ha-sig)

by Mairéid Sullivan (from the book, Celtic Women

in Music)

It

was announced in Dublin on October 2 that Máire Ni Chathasaigh

is the recipient of the TG4 National Traditional Music Award for Musician

of the Year 2001 (the highest possible honour for a traditional Irish

musician), to be presented at a live televised awards ceremony in the

Cork Opera House on November 17th. (TG4 is Ireland's Irish-language TV

station.) The citation says: "For the excellence and pioneering force

of her music, the remarkable growth she has brought to the music of the

harp & for the positive influence she has had on the young generation

of harpers". The previous three recipients of this award were Matt

Malloy, Tommy Peoples and Mary Bergin, so she's in good company. It

was announced in Dublin on October 2 that Máire Ni Chathasaigh

is the recipient of the TG4 National Traditional Music Award for Musician

of the Year 2001 (the highest possible honour for a traditional Irish

musician), to be presented at a live televised awards ceremony in the

Cork Opera House on November 17th. (TG4 is Ireland's Irish-language TV

station.) The citation says: "For the excellence and pioneering force

of her music, the remarkable growth she has brought to the music of the

harp & for the positive influence she has had on the young generation

of harpers". The previous three recipients of this award were Matt

Malloy, Tommy Peoples and Mary Bergin, so she's in good company.

BIOGRAPHY

Máire Ní Chathasaigh is "the most interesting &

original player of our Irish Harp today" (Derek Bell). She grew up

in a well-known West Cork musical family and began to play the piano aged

six, the tin-whistle aged ten and the harp aged eleven. Using her knowledge

of the idiom of the living oral Irish tradition, she developed a variety

of new techniques, particularly in relation to ornamentation, with the

aim of establishing an authentically traditional style of harping: she's

been credited with "a single-handed reinvention of the harp".

Her originality was quickly recognized and she made a number of TV and

radio broadcasts as a teenager, going on to win the All-Ireland and Pan-Celtic

Harp Competitions on several occasions in the 1970s. In 1985 she recorded

the first harp album ever to concentrate on traditional Irish dance music,

The New-Strung Harp, described by The Cork Examiner as "an intensely

passionate and intelligent record... a milestone in Irish harp music".

Her unique approach to her instrument has had a profound influence on

a whole generation of Irish harpers.

A book of her harp arrangements The Irish Harper was published by Old

Bridge Music in 1991. 'If Máire weren't around, Irish harping would

be so much the poorer… Her work restores the harp to its true voice"

- The Irish Times.

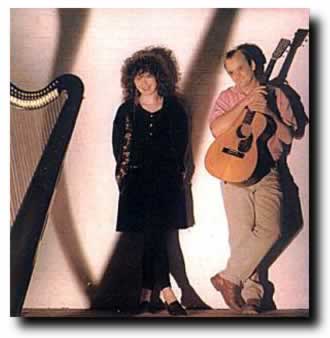

Her musical partnership with Chris Newman, one of the UK’s more revered

acoustic guitarists, made its début at the 1987 Cambridge Folk

Festival. “Virtuosic, fascinating, dramatic, original, inspired,

gloriously adventurous, dazzling, brilliant, stunning, impassioned, electrifying,

bewitching, moving, achingly beautiful, influential, revered, unique”

are just some of the adjectives which have been used to describe their

music (by The Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, The Irish Times,

The Scotsman and Folk Roots). They’ve played in twenty-one countries

- from the Shetland Islands to New Zealand, from San Francisco to Calabria

- and have given TV & radio performances on five continents. Though

rooted in the Irish tradition, the eclecticism, emotional range and spirit

of adventure of their performances, a breathtaking blend of traditional

Irish & Scottish music, hot jazz, bluegrass & baroque, coupled

with Máire’s “clear, warm & expressive voice”

& Chris’s “subversively witty introductions” continue

to ensure a busy performing schedule. The most recent of their four critically

acclaimed albums together Live in the Highlands “captures the essence

of these remarkable performers in a rare and priceless way. Absolutely

essential.“ - Folk Roots.

Máire and Chris are also featured on Celtic Harpestry, a major

Celtic harp album & associated TV special recently released by Polygram

USA & currently listed on the Billboard Chart. The Goldcrest feature

film Driftwood features Máire's singing over the closing credits,

and her harping & compositions feature with other luminaries of the

Celtic music world on the major Sony (France) album Finisterres by Dan

ar Braz et I'Héritage des Celtes, which recently received a Gold

Disc. Missa Celtica, a new work by English composer John Cameron has just

been released on Warner Classics, and features the New English Chamber

Orchestra, the Choir of New College Oxford and a number of soloists -

including Máire, on harp and voice. She’s currently working

intensively on a new solo album.

INTERVIEW with Máire Ní Chathasaigh

M.S. How did you first discover the harp, Máire?

M.NiC.

Well I’m not really sure how I did. I grew up in a very musical family.

There has been a very long tradition in both my mother’s and my father’s

families. My mother is from Allihies, in West Cork, right at the tip of

the Beara Peninsula. That’s not far from where you come from. Her

mother was O’Dwyer and she is an O’Sullivan. There have been

fiddle-players in the O'Dwyer family for the last two hundred years. My

mother and grandmother were singers. M.NiC.

Well I’m not really sure how I did. I grew up in a very musical family.

There has been a very long tradition in both my mother’s and my father’s

families. My mother is from Allihies, in West Cork, right at the tip of

the Beara Peninsula. That’s not far from where you come from. Her

mother was O’Dwyer and she is an O’Sullivan. There have been

fiddle-players in the O'Dwyer family for the last two hundred years. My

mother and grandmother were singers.

M.S. Someone told me that there aren’t a lot of the old sean-nós

songs, that are specifically written for women singers, left in Ireland,

because most of the collectors were men collecting from men. I wonder

whether your mother and grandmother knew any of the old Gaelic sean-nós

women’s songs, too.

M.NiC. They really didn’t seem to me to make a distinction on the

basis of gender. If they liked a song, they sang it regardless of whether

it was a written from the angle of a man or a woman. That’s always

been part of the tradition.

But to get back to your question about how I discovered the harp. My mother

started me playing the piano when I was six. Then I started playing the

fiddle for a while and then the tin whistle. When I was eleven I started

playing the harp. My mother has told me that I’d always wanted to

play the harp from the time that I was very small, though I’ve got

no memory of this myself – my memories of my childhood are quite

patchy really. She says that they could never figure out why the harp,

particularly, or where I’d even heard one! So when the opportunity

came up, they bought one for me. I’ve discovered since that quite

a few harp players I know had the same experience: they’d always

wanted to play the harp from when they were really tiny. My sister, Nollaig

Casey, and I started the harp at the same time. We both started the fiddle

at the same time as well, but though I’ve always loved the fiddle,

I was more drawn to the harp. I just seemed to have a very strong natural

affinity for it – and I'm now a professional harper, while Nollaig

was drawn to the fiddle and is now a professional fiddle-player!

On my father’s side of the family, there has been an enormous tradition

of Seanchas (shanahus) which means lore and learning of all kinds: historical

information, genealogical information, heroic tales, poetry. My father

can trace his maternal ancestry, purely in the maternal line, back to

the sixteenth century. That is an oral tradition: it's never been written

down. That is the sort of thing they preserved in my father’s family.

Many of them, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, were poets in the

Irish language. Some of the poems they composed were preserved in the

form of songs, which were still sung in West Cork up until the 1930s.

As a child I remember learning a few of what are often described as "occasional

verses" from my father. I remember learning one in particular, a

humorous extempore verse composed by a nineteenth-century ancestor of

mine, Donncha Óg Ó hIarlaithe, where he pokes fun at his

daughter who liked staying in bed late in the mornings. It was passed

down orally in the family - it's never been written down. It's full of

puns and word play, which don’t work so well when translated. Apart

from anything else, it sounds perfectly OK in Irish, but when translated

seems very vulgar all of a sudden! Irish is a very earthy language.

My

father’s grandfather was apparently a very fine singer and the family

tradition is that some songs were collected from him by George Petrie,

the famous nineteenth century collector of traditional music. So, on both

sides of my family there’s been a very long tradition of knowledge

of all sorts of Irish artistic activities, like composing poetry, playing

music, preserving historical and genealogical information and lore of

all kinds. My

father’s grandfather was apparently a very fine singer and the family

tradition is that some songs were collected from him by George Petrie,

the famous nineteenth century collector of traditional music. So, on both

sides of my family there’s been a very long tradition of knowledge

of all sorts of Irish artistic activities, like composing poetry, playing

music, preserving historical and genealogical information and lore of

all kinds.

I grew up steeped in this. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I

realized how very unusual it is to know so much about your own lineage:

lots of people, even in Ireland, know very little about their background,

their ancestors, where they came from. I think that this feeling of connection

to the past is probably one of the reasons that I feel so passionate about

the music that I play. I feel a very strong affinity and love for all

aspects of the Irish tradition and Irish culture, not just music, inspired

purely by the family I was born into and its long collective memory –

a long artistic collective memory which reaches back over two hundred

years. My father himself, although he's a highly literate and learned

man, has an extraordinary memory. It's the sort of memory which was probably

once common in pre-literate societies, but which is now incredibly rare,

probably because it’s no longer necessary. I remember him once declaiming

a forty-verse poem which he’d learned from an old neighbor in the

1930s: he’d only heard the poem twice but was able to remember every

word of it! I’ve always been completely in awe of this gift, but

unfortunately I haven’t inherited it. He’s always been a voracious

reader and his extraordinary memory also means that he’s forgotten

very little of what he’s ever read – he told me once that he’d

memorized three of Shakespeare’s plays by the time he was fourteen

years old. On the other hand, he’s never been able to remember what

he did yesterday, or where he put his car-keys! He’s now eighty-five

and his memory is not what it used to be – it’s been fading

for the last few years – but it’s still remarkable.

My father grew up in quite a remote part of the parish of Caheragh, between

Skibbereen and Bantry. His family was the last family of native Irish

speakers in the district, because his grandmother was still alive when

he was a little boy: she’d lived through the Famine, and wouldn’t

allow any English to be spoken in the house because she blamed the English

for the Famine. That’s one of the reasons why so much lore was passed

on.

M.S. I had an aunt over near Caheragh, her maiden name is O’Sullivan,

and they spoke Irish at home all the time, too. I used to spend my school

holidays there, playing with my cousins.

I wanted to ask you something about your O’Sullivan family ancestors.

They would have been related to the O’Sullivan Beara family, from

Cork, who were the last to stand in battle against the English?

M.NiC. Well, the O’Sullivan Beara clan kept on fighting after the

battle of Kinsale, until they were completely defeated. They never surrendered.

The O'Sullivan Beara's retreat to Leitrim was described in Irish as a

cúl-throid, or "fighting retreat".

M.S. That’s the same family, then. While some of the survivors moved

to Spain and served the Spanish court after their defeat by the English,

I would imagine the remaining members of the family would have been inspired

by a very strong sense to hold on to the culture. Especially since they

were the last ones to lead the battles to preserve it.

M.NiC.

I would imagine, as well, that it would have been possible for the O’Sullivans

of the Beara Peninsula to keep their culture longer because the terrain

they lived in was very remote and inaccessible. A cousin of mine recently

read the memoirs of an eighteenth century traveler in the Beara peninsula.

This traveller said that he’d never come across a people who believed

so much in fairies and the otherworld. When we were growing up, we spent

our holidays every summer with my mother’s family in Allihies, and

while we were there, we’d always go to visit my great uncle, my grandmother’s

brother, Mike O’Dwyer, who lived across the mountain in Urhan. He

was a great storyteller, he was blind, and he used to tell wonderful stories

about his own encounters with the fairies. As children, our eyes used

to be as big as saucers. We were completely spellbound. And of course

we were excited and frightened too! I still remember the atmosphere in

the house with the family all gathered together around the fire and the

wind howling outside. Sometimes, just out of devilment, Uncle Mike would

make up stories as well, just to frighten us – until we heard the

adults all roar laughing! Then we realized we'd been had. All of the older

generation of my relations believed in fairies. They all believed in the

spirit world. M.NiC.

I would imagine, as well, that it would have been possible for the O’Sullivans

of the Beara Peninsula to keep their culture longer because the terrain

they lived in was very remote and inaccessible. A cousin of mine recently

read the memoirs of an eighteenth century traveler in the Beara peninsula.

This traveller said that he’d never come across a people who believed

so much in fairies and the otherworld. When we were growing up, we spent

our holidays every summer with my mother’s family in Allihies, and

while we were there, we’d always go to visit my great uncle, my grandmother’s

brother, Mike O’Dwyer, who lived across the mountain in Urhan. He

was a great storyteller, he was blind, and he used to tell wonderful stories

about his own encounters with the fairies. As children, our eyes used

to be as big as saucers. We were completely spellbound. And of course

we were excited and frightened too! I still remember the atmosphere in

the house with the family all gathered together around the fire and the

wind howling outside. Sometimes, just out of devilment, Uncle Mike would

make up stories as well, just to frighten us – until we heard the

adults all roar laughing! Then we realized we'd been had. All of the older

generation of my relations believed in fairies. They all believed in the

spirit world.

M.S. That’s how it was where I was brought up as well.

M.NiC. Two of my uncles were very psychic and two or three of my cousins

in this generation are psychic too. Psychic ability was very strong in

my mother’s family: I think it came from my mother’s father’s

side, the O’Sullivan side. I’m quite telepathic and trust my

intuition to guide me in everything, but I’m not psychic myself.

One of my brothers is a bit, I think. Funnily enough, he’s the one

who physically most resembles the O’Sullivans. I don’t regret

not having the ability: it doesn’t always bring happiness.

M.S. What I have learned about that is that it a function of the way you

use your brain vibrations, alpha, beta, etc. Some people learn that and

others are predisposed to being much more open and perceptive, They are

more sensitive. In our rigid world we have a tendency to tighten or narrow

our perceptive focus.

M.NiC. Those born with a natural talent are more open to it. So, from

both sides of my family, that is the sort of background I came from. It

is very much linked to the past. I had a very rich cultural setting for

the development of my talents.

M.S. Was the Catholic Church very strong in your family?

M.NiC. It’s a completely natural part of everybody’s life in

Ireland.

M.S. Is it separate from the other beliefs they held on to?

M.NiC. No it isn’t. It could perhaps be interpreted as an extension

of the ancient belief in the otherworld and the associated belief in the

centrality of a spiritual dimension to life that we were just talking

about. Several members of my mother's extended family were nuns and priests,

which is probably not accidental. I have an aunt who's a nun, a very serene

and spiritual person, who's also quite psychic I think.

Christianity in Ireland is shot through with all sorts of other beliefs

that have nothing to do with Christianity. Most people in Ireland think

they are Christian beliefs. At least the old people thought they were.

In fact, they are pre-Christian beliefs that are completely wound up with

Catholicism. If you actually examine them you will find that they have

nothing to do with the Church at all, but the people, themselves, are

convinced that they are.

Celtic Christianity developed in its own way over many centuries in relative

isolation, incorporating within it many aspects of a pre-Christian, pagan

Celtic belief system, before it was made to conform to Roman practices

in the 12th century - though even then it was never completely stamped

out. Because Celtic Christianity was so inclusive of all sorts of ancient

beliefs, these beliefs were remarkably tenacious and survived in Ireland

until the twentieth century.

The rigidity that is associated with the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century

Irish Church is a post-Famine phenomenon, a reaction to the severe psychological

trauma inflicted on the whole country by the Famine. People were terrified

that it might happen again. Whereas before the Famine most people married

young, after it, people were afraid that they mightn't be able to feed

their children. So very often only one member of the family inherited

the land and married and had children. The other siblings either remained

unmarried on the family farm or emigrated in the hope of earning enough

money to be able to marry. The Irish people were never puritanical; the

Irish language is not a puritanical language, even today. The Puritanism

that some people associate with the Irish Church is an extremely recent

thing, which developed purely as a consequence of the Famine; it was aided

and abetted of course by the huge decline in the Irish language after

the Famine. When people became more exposed to English they also became

more exposed to the stifling influence of Victorian England. Puritanism

wasn't a cultural feature of pre-Famine Ireland. It's interesting that

if you speak to native Irish speakers they'll express themselves in Irish

with enormous freedom, in a way that they never would in English. The

freedom of expression characteristic of the Irish language is not acceptable

in English, even today. Irish is a very earthy language and the Irish

people were very earthy, but spiritual too.

M.S. Do you think the traditional music is affected by that stoical restriction?

M.NiC. Oh no! Well certainly not now. During the heyday of the puritanical

phase of the Irish Church in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some

puritanical priests put a stop to crossroads dancing and house dances.

The great collector of Irish traditional dance-music, Francis O'Neill,

who, like my father, was born in the parish of Caheragh, was full of resentment

about this. He says in his book, Irish Minstrels and Musicians, that a

piper he knew in the parish who made his living from playing for dances

was thrown into poverty as a result of the ban and ended his days in the

workhouse, and that a number of other musicians he knew emigrated out

of despair. But Irish people have always had a great joie de vivre, a

great delight in being alive which can never be repressed for long. Neither

the trauma of the Famine nor clerical misguidedness managed to crush their

spirit completely: the minute it got a chance again it bubbled up. So,

no. I don’t think it has affected the music long-term. Obviously

a lot of musicians must have died in the Famine and thousands more emigrated.

The music could have died, but miraculously, it never did.

M.S. What do you think is the source of that natural spring of energy,

that joie de vivre, as you say?

M.NiC. It was always there, but there have been an awful lot of traumas

in the last few hundred years of Irish history which have repressed it

for a while. The Cromwellian wars were very traumatic, the forced movements

of population and the huge massacres. For example in 1649 thirty thousand

people just in Drogheda, were put to the sword by Cromwell’s soldiers.

The Penal Laws were appalling. Things calmed down for a bit and then came

the Famine, the most recent large-scale trauma. The Irish psyche has always

recovered and bubbled to the surface again. The current generation is

now ‘back not normal’, you could say. Irish culture, in itself,

has always been very expressive, very free, and very unfettered, very

unrepressed. Sometimes you meet people who, in themselves, are damaged

by very rigid nuns or priests who taught them, thirty or forty years ago.

They have blamed the Church for ruining their lives. That doesn’t

mean anything to me, really, because I grew up after The Second Vatican

Council. I think there is an enormous difference between people who grew

up after and before The Second Vatican Council. That is because the whole

way of approaching religion completely changed. Hell didn’t mean

anything to me when I was growing up. The way religion was taught before

that was very authoritative, whereas after, it was much looser and freer.

It was much more participative. There was much less fear. So, I don’t

associate the Church with being afraid. My view of it is as a benign force,

not a malign force. People, who are twenty years older than me, in their

sixties, who talk about how they were mistreated and damaged by the Christian

Brothers, etc., might as well be talking about two hundred years ago,

as far as I am concerned. That bore no relationship to the way I grew

up. It doesn't mean of course that I want to belittle their pain in any

way.

There has always been, in Irish culture, an enormous exuberance of spirit

which external events have crushed from time to time, but we’ve always

bounced back from that because our culture is so incredibly strong: The

springs of creativity in us are so strong. A part of our whole identity

as people is a creative identity. Creativeness is completely central to

who we are.

I do an enormous amount of travelling and I have not seen any other country

where the ability to do something artistic is so highly valued. I live

in England now, and though we are very successful in what we do, this

society’s view of musicians is that they are not perceived to be

appreciated as much as in Ireland, where an artist is revered. If you

are a musician, you are down a bit in the social pecking order, rather

than up at the top.

M.S. Wouldn’t that be related to the royal hierarchy?

M.NiC. No, it’s not that, actually. It’s something extremely

fundamental. You see, in early Irish society, as among other Celtic peoples,

the file or poet had the same status as the king. The word file originally

meant a seer or wise man, and the file retained some of the prestige of

the druid. In the very earliest times, the druids were the highest class

in society, just like the Brahmins were in India. Because the poets had

a very high status in society, what they said was revered. In the earliest

periods they were considered to have the ability to bless or curse. In

the mediaeval period every chieftain had his own hereditary professional

court poet, whose main function was to praise the deeds of his chieftain

in panegyric or praise poems. The poet could, equally, if he didn’t

like what the chieftain was doing, write an ‘aor’ or satire,

to criticize the king or chieftain. In the earliest periods, this was

considered to have the power of a curse. So, the power of the word and

of the creative person producing new words was enormous. That is a very,

very ancient tradition.

The harpers had a very high status in society as well, but not as high

as the poets did. Whereas in the earliest times the poets had the same

status as the kings, the harpers were freemen - the only class of musicians

who were allowed to become freemen! The word was always the main thing

in Ireland. All of the descriptions of Celtic society talk of their love

of poetry and their love of music. It is intrinsic to our sense of ourselves.

There was a high-ranking Norman/Welsh monk called Giraldus Cambrensis,

whose uncle Maurice Fitzgerald was one of the principal leaders of the

Norman invasion of Ireland, who visited Ireland in 1185 in the retinue

of Prince John, the youngest son of King Henry II of England. While he

was there he wrote Topographia Hiberniae (The History and Topography of

Ireland) which is very interesting. He didn't travel very widely in Ireland,

so some of what he wrote is based on hearsay, and of course it's colored

by the fact that he came to Ireland with a conqueror. He was very credulous

and seems to have believed every tall tale he was told by the locals!

Maybe he thought he was such a superior being that he couldn't believe

that anyone would dare to pull his leg. It's always in the interest of

conquerors to disparage those who are being conquered. Giraldus's natural

tendency would be to disparage everything he saw. He thought we were a

barbarous people, with far too great a love of leisure and liberty, who

spent ridiculous amounts of time listening to music and poetry. He thought

this was a waste of time. What he said was absolutely true of the native

Irish aristocracy, who despised manual labor. They believed in using the

lower orders and plenty of slaves to do all the donkey-work, leaving them

free to devote their time to the finer things in life, like making and

appreciating art of all kinds.

Slavery was apparently so widespread that the Irish bishops at a 12th

century synod in Armagh came to the conclusion that the Norman invasion

was the judgement of God on the Irish for their purchase and enslavement

of English people! Kind of ironic really. Anyway, Giraldus disparaged

plenty, but one of the few positive things he said is that he had never

seen harpers to compare with the Irish harpers. He said he'd never heard

such accomplished playing, anywhere. He described the music of the harp

as being highly ornamented and as being of an extraordinarily high standard.

Giraldus was actually a very sophisticated person, who had studied in

Paris and was familiar with all of the most advanced European literary

and artistic movements. The Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris was the center

of the avant-garde in music at the time, what is known as the Ars Antiqua,

"old art". This makes his testimony absolutely fascinating and

very valuable to us today. He wasn’t an ignorant observer. And since

his natural tendency would have been to disparage rather than praise,

the harpers he heard must have been truly extraordinary.

This love of ornament and decoration, which is very characteristic of

Irish music, still, to this day, has a very long history. Its part of

how we want to express ourselves. It’s completely part of us. I think

creativity has never happened just by chance in Irish society. I think

Ireland, by its very nature, has nurtured artists because it has always

appreciated them. You’ll find in even the smallest place, with people

who have never been anywhere, that they adore music. They have the greatest

regard for creative artists of any kind.

M.S.

It is so satisfying to hear that you have found that evidence. Let me

ask you about your harp. What kind of strings do you use on your harp? M.S.

It is so satisfying to hear that you have found that evidence. Let me

ask you about your harp. What kind of strings do you use on your harp?

M.NiC. It’s a nylon string harp. The harp that I play is, strictly

speaking, a neo-Irish harp. It looks like the ancient Irish harp but it

is strung with nylon strings. It can also be strung with gut strings.

M.S. Have you tried both sounds?

M.NiC. I specifically like the nylon. I’ll tell you why. When I was

in my early teens, I’d already been playing the whistle and the fiddle

and lots of different things. I grew up playing both traditional and classical

music, side by side. But what I wanted to do is play traditional music

on the harp. I wanted to play dance music on the harp, which hadn’t

been done before. At that point in Ireland, the harp was used mainly as

accompaniment to songs. There were hardly any harp teachers outside of

Dublin. There was nobody decent at all outside Dublin, actually. The harp

had become very much an urban instrument. It had become completely disassociated

with the oral tradition, with people who played music in the countryside.

The people who played dance music and slow airs, who were part of the

oral tradition, learnt the music orally.

The old Irish harpers played for an aristocratic clientele. A lot of their

music has survived in various collections, but it's very complex and sophisticated

and technically extremely demanding and it's not very accessible really:

it sounds a little strange to modern ears. It doesn’t sound like

what we now think of as Irish music. Another large chunk of the music

they played has survived in the oral tradition; for example the really

famous Irish airs like "The Derry Air" were almost certainly

composed by harpers. Most of these airs, like a lot of the current music

associated with Ireland, go back only two or three centuries and not further.

The harpers didn’t play dance music at all; in fact they would have

looked down their noses at people who played dance music because that

was the music of ‘the people’.

But that is what I always wanted to do because that is the tradition I

grew up in. I was playing the Uilleann pipes, which is an instrument that

I’ve always loved and which was my main inspiration. What I wanted

to do was to develop a way of playing that music on the harp, so in my

early teens I started developing the necessary new techniques of fingering

and ornamentation. I've been teaching people how to play dance music on

the harp since the mid-seventies. There are people who have learnt from

people who’ve learnt from people who have learnt from me a long time

ago. So now, there are hundreds of young harpers in Ireland, and elsewhere,

who use the techniques that I developed, and their own variants of them,

which is great.

M.S. You were the forerunner of that approach.

M.NiC. Yes. But to get back to your question about the nylon strings,

I started playing on gut strings. The second harp my parents bought for

me, when I was thirteen, was a Japanese-made harp. A Japanese man called

Kunzo Aoyama started to make nylon-strung Irish harps in the late sixties.

They also had thirty-four strings and a new, improved, way of changing

key, using up-and-down semi-tone levers. It was a much better system than

the one that was there before, much more suitable for instrumental music.

I thought it was absolutely fantastic. It was the sound of the nylon that

made me think I could make dance music work on this instrument. I couldn’t

have made it work on the gut-strung harp I had before, because gut has

a very mellow sound which, of course, is lovely if you want to accompany

songs and play slow music. If you want to play very fast dance music,

which has a lot of ornamentation, you need a much brighter sound, and

the nylon provided a very bright sound. So, that was the sound I was looking

for.

M.S. Did you find yourself playing the harp in sessions.

M.NiC. Yes, when I was a kid. I was a very shy teenager. I didn’t

like to play for people unless I was asked.

M.S. So your desire to play dance music wasn’t actually related to

your wish to play with everyone else.

M.NiC. No. It was nothing to do with that. It was more a personal, artistic

aim, for its own sake. I had always played with other people but not on

the harp. I always played the whistle in sessions and that. You don't

attract so much attention, which suited me fine! I would venture to say

that I find playing the harp with lots of other musicians, to be very

frustrating. I don’t feel I am contributing anything because I don’t

make enough noise. I always enjoyed playing with, maybe, a couple of other

people. Then it has an artistic purpose and you're interacting in a very

creative way.

M.S. How did people react when they heard dance music on the harp for

the first time?

M.NiC. I remember when I first entered the under fourteen All-Ireland

Fleadh Cheoil. Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann organizes

the Fleadh Cheoils every year. I got an awful lot of encouragement from

people I met at that time. People said they'd never thought they'd see

the day that they'd hear dance music on the harp. A lot of older traditional

musicians, at that time, thought the harp was a useless instrument, that

you couldn’t play anything decent on it. But once they heard what

I was trying to do they were immensely supportive and full of praise and

encouragement. They gave me the confidence to develop what I was doing

even further. There isn't of course anything at all wrong with the harp,

in itself, as a means of playing traditional music in an authentic style.

You just have to know the traditional music, you have to grow up with

it and be immersed in that style. Otherwise you're not going to play the

right thing. It doesn’t matter how good you are if you don’t

know the style. I grew up with the style and then developed the techniques

to transfer the sound I heard in my head onto the harp-strings.

M.S. You had the instrument that would allow you to play the music efficiently.

M.NiC. Yes. So, from then on I entered a lot of Fleadh Cheoils. I won

a lot of the competitions and got a lot of attention, because what I was

doing was very new. I appreciated that because when I was growing up I

was extremely shy. A lot of musicians, when interviewed disparage the

whole idea of competitions. I actually think that I would still be playing

to myself in my own front room if I hadn’t entered those competitions.

At that time, it really wasn’t the done thing for females to put

themselves forward. Male musicians have always been able to go into a

place and ask for gigs. At that time a female couldn’t do that. It’s

still more difficult for young females, though it's delightful to see

how much more confident the new young generation of female traditional

musicians is by comparison with my own.

M.S. When were you a teenager?

M.NiC. In the early seventies. If you enter a competition, as a girl,

and you win, basically it's an objective validation of what you’ve

done. Somebody else has said you are good. You don’t have to say

it yourself. You don’t have to push yourself, which a nicely brought

up young girl is not supposed to do. Even still, if you grew up in that

way, you can never really overcome that.

M.S. That is certainly true still.

M.NiC.

There are some people who are born pushy but most women are not, if they

are brought up in a particular way. In England, I am often asked, “Why

are there such enormous numbers of really wonderful Irish female musicians?”

There have been for the last thirty or forty years. I think one of the

reasons is that the whole competition system brought a lot of female musicians

to prominence when they were in their teens. A purely objective assessment

is made that you are the winner, the best, so the whole musical culture

hears about you. It benefited us females enormously. It brought us to

prominence without ourselves having to say that we were brilliant. It

gave a great boost to our self-esteem in those shaky teenage years and

the confidence to develop our talents even further. M.NiC.

There are some people who are born pushy but most women are not, if they

are brought up in a particular way. In England, I am often asked, “Why

are there such enormous numbers of really wonderful Irish female musicians?”

There have been for the last thirty or forty years. I think one of the

reasons is that the whole competition system brought a lot of female musicians

to prominence when they were in their teens. A purely objective assessment

is made that you are the winner, the best, so the whole musical culture

hears about you. It benefited us females enormously. It brought us to

prominence without ourselves having to say that we were brilliant. It

gave a great boost to our self-esteem in those shaky teenage years and

the confidence to develop our talents even further.

Sometimes you’ll hear people, almost always men, disparaging the

whole competition system. This annoys me as I think it's been of enormous

benefit to women in Ireland.

M.S. So, if you were good, people would come to find you.

M.NiC. Absolutely, I didn’t enter to win, necessarily, those events

also provided a very important social function. But, if you did win people

would seek you out.

M.S. I remember a poll taken in Dublin in 1976/77, and the tin whistle

was voted the most popular instrument in Ireland. Gael Linn obviously

realized they had to put an album of tin whistle music out. They approached

Mary Bergin and released her first recording of music on the tin whistle.

She said they found her through the competitions.

M.NiC. Mary Bergin's the best tin whistle player in Ireland. She's a phenomenal

musician, an amazing musician. It's interesting that she agrees with me

about the competitions giving us a forum. But, as well as that, the annual

trip to the Fleadh Cheoil, (music festival) was a fantastic thing for

children growing up in the country. I grew up in Bandon, which is very

Anglicized. There was no traditional music played there at all. In fact

we used to be laughed at for playing traditional music. It was so unfashionable

- something that is hard to imagine these days, when Irish music is so

fashionable all over the world it seems. Our family’s big, enormous

treat of the year was to go to the All-Ireland Fleadh Cheoil, because

there we would meet so many other musicians of our own age and interests.

It was our big social event of the year. Our excuse was that we had the

competitions to go into but they weren’t the real reason for our

excitement. The Fleadh had an enormous social influence: it was like a

yearly validation that we weren't complete freaks!

M.S. Where are you, today, in terms of your vision of what the past has

brought you to and where you want to go with that understanding?

M.NiC. I keep working, especially on the older music. I do a lot of composition

these days. My first solo album was in 1985. I’ve done four recordings

since, with Chris Newman. I am working on another solo album, at the moment,

completely solo. And of course I love performing. I get great pleasure

out of giving people pleasure. We do a lot of touring.

My original mission in life was, I suppose, to reintegrate the harp into

the oral Irish tradition, from which it had become separated in the last

few centuries. That is very much the case now, and that is an enormous

change.

I have always felt a mission to explain Irish music, not just to non-Irish

people, but also to other Irish people. Given half a chance, I will expound

my theories to anybody (laughter). I try to explain why Irish musicians

play the way they do and what the actual aesthetic of the music is. A

lot of people involved in Irish music play, but they can’t really

explain why they do what they do, very well. So, I feel it is necessary

to explain. If somebody asks me I simply launch into it.

M.S. Please, go ahead, the floor is yours.

M.NiC. My central belief about Irish music is connected to my belief about

Irish society, which I was talking about earlier on. It is that Irish

music has always been a miniature art. If you think of the music of Beethoven

as a landscape painting: his music is painted in broad strokes so that

you have long crescendos and diminuendos. In comparison, Irish music is

like a miniature painting. There are huge changes of dynamics within one

bar of music. Some people think there are no dynamics in Irish music.

If you take a reel for example, it’s seems the same from beginning

to end. In fact, there are enormous changes but they all happen on a tiny

scale. The overall sound seems the same from start to finish, but it isn’t.

It changes all the time. A really, really good traditional musician will

never play the same thing twice in the same way. There will always be

a slight change. But it will be done in a very, very subtle way. Subtlety

is completely central to the whole Irish aesthetic. For the Irish, artistry

equals subtlety, basically. One of the descriptions, from the earliest

times, of the art of the Irish poets states that, to them, art that conceals

art is the greatest of all. It was true of the Irish poets in the eighth

century; it was true of the harpers described by Giraldus Cambrensis,

in the twelfth century.

I’ve actually got the book, which quotes the twelfth century monk,

Giraldus Cambrensis, right here. I’ll read it to you. This is the

translation from the Latin.

“The movement is not, as in the British instrument to which we are

accustomed, slow and easy, but rather quick and lively, while at the same

time the melody is sweet and pleasant. It is remarkable how, in spite

of the great speed of the fingers, the musical proportion is maintained.

The melody is kept perfect and full with unimpaired art through everything...

with a rapidity that charms, a rhythmic pattern that is varied, and a

concord achieved through elements discordant. They harmonize at intervals

of the octave and the fifth… They glide so subtly from one mode to

another, and the grace notes so freely sport with such abandon and bewitching

charm around the steady tone of the heavier sound, that the perfection

of their art seems to lie in their concealing it, as if 'it were the better

for being hidden. An art revealed brings shame.'

M.S. Is it that the Irish have hidden their ancient aesthetics under the

current of the mainstream, and that it still is perceivably active?

M.NiC. The whole Irish cultural aesthetic is to venerate the subtle over

the obvious. The Irish cultural consciousness has always revered subtlety.

Before the Irish were ever under threat from an outside power they revered

the subtle. It’s a very ancient thing; it has nothing to do with

what has happened to us.

Giraldus goes on to say:

“Hence it happens that the very things that afford unspeakable delight

to the minds of those who have a fine perception and can penetrate carefully

to the secrets of the art, bore, rather than delight, those who have no

such perception - who look without seeing, and hear without being able

to understand. When the audience is unsympathetic, they succeed only in

causing boredom with what appears to be but confused and disordered noise.”

What this is basically saying is that to be able to appreciate the music

of the harpers, you need to be educated in that music: that it was a very

subtle art which needs to be appreciated. People, who really, really know

and can penetrate the art, experience an unspeakable delight on hearing

it. The same is actually true of a traditional fiddle player, for example,

in the twentieth century, especially of the older traditional musicians.

If you hear them describing music, what they really respect in other musicians,

is subtlety. Not obviousness, not variations that jump up and scream at

you, as if to say, “I am a variation, look how brilliant I am.”

What they absolutely love, in the playing of other musicians, is subtlety.

It's interesting that that should be as true of musicians of the twentieth

century as it was of the harpers in the twelfth century. That whole view

of the nature of art is very ancient and very Irish. In the case of the

visual arts, just look at the old and very, very beautiful jewelry that

was made two to three thousand years ago. Likewise, objects like the Ardagh

Chalice, the Tara Brooch and the Book of Kells, which were produced in

the eighth century, when Irish art reached a peak of virtuosity. All the

illuminated manuscripts produced from the 6th century onwards were highly

ornamented, but the Book of Kells, which was the most famous illuminated

manuscript of all, was extraordinarily lavishly ornamented. But again,

you look at a page and the whole looks beautiful but it is so detailed

that even if you look at one tiny bit by itself it'll have something interesting

to say. For example, a tiny little figure inside a Capital letter might

be doing something interesting. That’s very much, again, a miniature

art. And, again, subtlety is exalted over the obvious. Giraldus Cambrensis

described the Book of Kells as being "the work, not of men, but of

angels".

M.S. Have you looked into the history of those manuscripts at all? Someone

was saying that those books are a hybrid of eastern and western design.

M.NiC. Well yes, though their motifs show striking parallels with Irish

jewelry and metalwork. Irish monasteries seem to have kept in close contact

with the very earliest monastic foundations, those of the Near East, particularly

Egypt and Syria. One characteristic feature of the Irish manuscripts,

which was also found in Egyptian Coptic manuscripts, is the surrounding

of capital letters with decorative red dots. It's been a feature of Irish

manuscripts since at least the 6th century and appears at about the same

time in Byzantine manuscripts. The extraordinarily beautiful "carpet

pages" also seem to have been inspired by Coptic models. What is

interesting, of course, is that Celtic society, particularly Irish society,

preserves a way of life which is very ancient. The Romans never conquered

Ireland, so it was able to preserve its Celtic culture in a pure form.

The Celtic languages are a part of the Indo-European family of languages.

One of the interesting things to observe is that the structure of ancient

Aryan society in India, which is described in the Rig-Veda, is the same

as the structure of society described by the early Irish writers. So that,

in a way, Ireland preserved a very ancient form of society, shared with

the ancestors of both the Indian culture and the Celtic culture.

M.S. The Vedas, are said to have been taken to the East, to India, fifteen

hundred years BC.

M.NiC. The Indo-European peoples are said to have originated in the steppes

of southern Russia, between the Caucasus and the Carpathian Mountains

and spread from there east to India and west to Europe. They're supposed

to have reached Central Europe around 3000 BC and the Punjab in India

between 3000 and 1500 BC. Presumably they brought the Vedas with them

to India. Ireland has always been consciously conservative; I mean that

in the positive sense of preserving things from the past. Preserving a

type of society. The society described in the old Irish law tracts is

a very ancient type of society, which is also described in the early Indian

tracts. It isn’t because Irish society was based on Aryan society

in India. It is that ancient Indian and Celtic societies were both the

descendents of an original Indo-European society.

M.S. Well said.

M.NiC. Thank you. There are some parallels between the Book of Kells and

the art of the Middle East, but that doesn't mean that one directly influenced

the other. I don’t think it’s as simple as that. The exaltation

of the subtle and the importance of ornament are two things that go back

a long way in Irish society. The Continental Celts were very much admired

by the Romans for their eloquence and their polished and artistic speech.

If you look at Irish poetry, it's very clear that it's always been very

highly ornamented, even when the structure changed drastically at various

times. There was enormous change in Irish society after the defeat of

the Irish at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601. Later in the seventeenth century

came the Cromwellian wars, which caused one of the real seismic shifts

in Ireland. In the hundred years after 1601 eighty-five percent of Irish

land was forcibly transferred into the hands of the new English colonists

and the old Irish aristocratic order collapsed. The chieftains were no

longer in a position to support either harpers or poets in the style to

which they had become accustomed.

The poets then had to change the style of poetry they composed, practically

totally. The harpers changed what they played, also, because now, in very

short order, they had to find new audiences. Because the music and the

poetry were actually aimed, very much, at a cultured and learned audience,

they now had to aim what they were doing at everybody, so they had to

change what they did quite drastically. The court poets of the medieval

period, and right down to the seventeenth century, composed mainly praise

poetry, but it was extremely formal. They used a lot of very complex meters,

for example. The used complex forms of word ornament. They also used a

standardized language.

That’s an interesting thing, which shows the continuity and conservatism

of Irish society. From the twelfth to the end of the sixteenth century

the Irish language, the Gaelic language, was standardized in grammar and

spelling. It was the first standardized vernacular (non-Latin) language

in Europe. It was standardized in grammar and spelling long before English

was, for example. This language was used by the learned classes and poets

both in Ireland and in Gaelic speaking Scotland. A poet writing in Gaelic

in twelfth century Scotland would be completely understood by someone

writing in Ireland in the sixteenth century, because they used exactly

the same language, the same grammar and spelling.

Old Irish and Modern Irish seem quite a long way apart, but you can see

how the language developed quite clearly. The earliest surviving examples

of written Old Irish are in the form of glosses, or explanations written

by an Irish monk in the margins of a manuscript of the Gospels in Latin,

which is preserved in the library of the cathedral of St Gallen in Switzerland.

The monks also wrote some lovely poems in the margins when they got bored

with copying out Gospels. There's one particularly sweet one, which a

monk wrote about the antics of his cat, Pangur Bán.

St. Gallen is an Irish Medieval settlement, a monastic foundation of St

Gall, built during the Dark Ages. After the fall of the old Roman Empire,

civilization collapsed in Europe, even royal families became illiterate

and knowledge of the ancient learning of Greece and Rome practically disappeared.

Irish monks re-civilized Europe between the sixth and the eighth centuries

by founding monasteries and teaching all over Europe. St Columbanus founded

a monastery in Bobbio, south of Milan, around 590; St Gall was one of

his disciples. St Colmcille founded the monastery of Iona in Scotland

in about 561. Irish missionary work in England began with the foundation

of an abbey at Lindisfarne by St Aidan who came from Iona in 635. Another

Irishman, St Killian, was a missionary at Würzburg in Germany, where

he was martyred in 689. And so on, etc.

M.S. Tell us more about the poets?

M.NiC. As I said earlier on, after the collapse of the old Irish order

in the seventeenth century, the poets abandoned writing in the standardized,

classical language in order to compose poetry in the language of the people,

the dialects of the regions they lived in. The structure of the poetry

they started to compose changed completely as well. Instead of the very

formal court poetry, which was based on the number of syllables in the

line, and complex schemes of rhyme and alliteration, they started to write

poetry, which had more of a song meter. They abandoned the syllabic poetry.

Even though the whole form of the poetry changed, it retained the very

beautiful, very musical, very highly ornate style. The importance of ornament

was retained. The very same thing happened with the harp music. The famous

harper, Turlough O'Carolan, exemplifies this transitional period in music.

His music is a hybrid of the more ancient Irish court music and the music

that was popular in contemporary Europe, the music of the baroque style.

Again, the harpers wanted to make their music accessible to the new landowners,

who were of English origin and, of course, to the ordinary people as well.

But they retained their love for ornamentation and variation, and for

subtlety in expression. Even though the forms changed over the centuries,

the bedrock of the tradition never changed. That’s why I believe

there is a specifically Irish aesthetic. It’s an aesthetic, which

reveres the subtle over the obvious, and is expressed in every art form.

The artistic impulse has remained the same down through the ages.

One of the things that worry me slightly is that this aesthetic may not

survive modern methods of mass communication and the drive towards homogeneity

in music. This applies even within traditional music, with everybody hearing

the same thing, played over and over, the same way, on recordings. It

runs against the individualism, which is very much part of the Irish tradition.

The harp and the Uilleann pipes are solo instruments in the tradition.

They are about an individual making an artistic statement. The modern

world obscures this slightly, but it is still very much there. There's

still an enormous number of discriminating listeners to Irish music who

will prefer hearing a solo player, to hearing a bunch of people playing

together, because then you can really hear the variations going on and

that’s what they look for in the individual interpretation.

I feel that this whole perception of the nature of the music, of why musicians

do what they do, is seen in so many other Irish art forms and goes back

so far, that it is central to who we are. I say this over and over again

because I really believe it. My primary aim is to draw people into the

music in a more meaningful and deeper way, so that they can hear beyond

the surface.

| This interview is an excerpt

from Mairéid Sullivan's book, Celtic Women in Music.

Reprinted with the permission of the author. Please click

here to find out more about this

fascinating book. |

Subject: Terms for publishing articles by Mairéid

Sullivan. There is of course no charge for viewing the full text of any

article

on this site. To request an article or articles for reading, publishing

or syndication, simply submit an email

clearly outlining titles or key words of the features that interest

you. In doing so, you are agreeing that all text and images transmitted

electronically remain, and will remain at all times, the exclusive property

of Mairéid Sullivan. Articles may not be reproduced without first

entering into a contract based on the terms described in this paragraph.

Terms of sale / publishing are subject to negotiation depending on international

copy and picture rates, but generally, a base rate US. $100. IR£100

(EUR126.97) per 1,000 words, and U.S.$25. IR£25 (EUR31.74) per photograph

/ illustration. There is no charge for individuals wishing to obtain articles

for their own private use.

Máire Ní Chathasaigh DISCOGRAPHY

Máire Ní Chathasaigh (solo)

The New Strung Harp, Temple Records 1985

Máire Ní Chathasaigh & Chris Newman

The Living Wood, Old Bridge Music 1988

Out Of Court, Old Bridge Music 1991

The Carolan Albums, Old Bridge Music 1994

Live In the Highlands, Old Bridge Music 1995

COMPILATIONS

The 5th Irish Folk Festival, Wundertüte (Germany), 1978

The Best of the Irish Folk Festival, Wundertüte (Germany), 1988

The Best of the Irish Folk Festival Volume 2, Wundertüte (Germany),

1989

Bringing it All Back Home, Hummingbird Records, 1991

A Celtic Treasure, Narada Media (USA), 1996

L'Imaginaire Irlandais, Keltia Musique (France), 1997

Finisterres: Dan ar Braz et l'Héritage des Celtes, Sony (France),

1997

Celtic Harpestry, Imaginary Road Records (USA), 1998

Also voice and harp soloist on Missa Celtica by John Cameron, released

on Warner Classics.

Website:http:// www.oldbridgemusic.com

|

![]()

![]()